If you’re not from the U.S or you’re part of a younger U.S generation, you might not have a lot of personal experience with checks—a paper-based method of money transfer. They’re rapidly going out of style as newer electronic payment methods become more convenient and secure, but they’re far from gone: a lot of infrastructure and habits have been built around checks in the U.S. But how do checks work?

The basic concept is simple: an individual or a business writes down an amount of money and a recipient on a piece of paper issued by a bank. The recipient deposits the check, the banks initiate a transfer between accounts, and the transaction is complete. There are a lot of different types of checks, though, several behind-the-scenes steps between Person A writing a check and Person B getting money.

What’s a check? How does it work?

At its most basic, a check is just an IOU saying that the payer (the person writing the check) is promising the payee (the recipient of the check) a certain amount of money from their bank account. The vital elements of a check are:

- Payer name

- Payee name

- The payment amount (in numeric characters)

- The payment amount (in alphabetic characters)

- A routing number, which identifies the payer’s U.S bank

- An account number, which identifies the payer’s bank account

The only information required about the payee is their name since the payee will be identified by the bank where they deposit the check later.

Checks are actually an ancient technology: they may have been used in ancient India and Rome as early as 300 BC and were first issued in preprinted form by English banks in the 18th century. Many countries have used checks in some form or another, but the U.S is the largest country where they remain common. American payment systems, like the rest of the world, are evolving towards the electronic, but the continued prevalence of checks points to the progress these systems still have to make.

How exactly do checks work?

The basic idea is simple enough: a bank or network of banks holds money on behalf of the payer, who then transfers it to the payee by authorizing his bank, to deliver some portion of his money. The life cycle of a personal check (by far the most common type) looks like this:

-

- The payer writes a check from their bank (“Paying Bank”) to the payee, filling out either their name or just writing “cash,” which allows anyone to deposit the check.

- The payee goes to their own bank (“Receiving Bank”) and deposits the check, or uses mobile check deposit to send images of the check to their bank electronically.

- Receiving Bank sends Paying Bank a payment request (an electronic image of the check), or, if there isn’t a direct financial relationship, it sends the request to a clearinghouse (likely the Automatic Clearing House, or ACH, system), which acts as a middleman for the involved banks.

- Receiving Bank makes the funds, or some portion of the funds, available to the payee, generally before the check has cleared (i.e, before the money has actually been transferred from the payer’s account at Paying Bank to the payee’s account at Receiving Bank)

- Receiving Bank sends a request to Paying Bank to pay the specified funds.

- Paying Bank deducts funds from the payer’s account and transfers them to Receiving Bank, after which the check has cleared and the process is complete.

To put it more simply, a customer from one bank gives a customer from another bank an IOU. The person who holds the IOU goes to their bank and gets the money. The IOU-holder’s bank tells the IOU-writer’s bank that they’ve got to pay up, which they then do by taking money from the correct account. This process generally takes about 2-3 days, depending on the banks’ relationship and the type of request.

The money usually appears in the payee’s account instantly or within a few hours, but until the check clears this money is only “available,” not actually guaranteed. If the payer turns out not to have enough money in their account, the money will be taken back from the payee’s account, even if it has already been spent, though, so it’s a good idea to wait for checks to clear before spending the money.

Most of the time personal checks are good for around three to six months, and there is no legal limit on how much money they can be written for. They also don’t have to be deposited physically anymore, since mobile check deposit allows users to take pictures of the front and back (with their signature) of their checks with their mobile phones and submit the images to their bank through apps.

What about other types of checks?

Every U.S check works basically the same way, with some minor differences. Personal checks are by far the most common, but there are a lot of other types that can be used in different situations.

-

-

- Bearer checks: These are just ordinary checks made out to “cash,” and can be very risky since they can be cashed by anyone, even someone who just picks them up off the street. They are useful if you need a cash instrument that you can transfer between multiple people, but generally not advised.

- Cashier’s checks: These checks are handy because they’re guaranteed by the bank that issued the check. The payer’s account is generally debited immediately, or the payer simply pays in cash. When the payee deposits the check it clears instantly because their bank is assured of payment.

- Certified checks: This is when the bank certifies that the payer has enough funds in their account to cover the check and that the signature is genuine. The bank will then withdraw and hold the funds in escrow until the check is cashed at another bank. This is similar to a cashier’s check.

- E-checks: The electronic check is the U.S’s answer to online bank transfers. It works very similarly to a paper check—which are themselves often converted to e-checks by businesses and banks. They use the ACH electronic payment system to initiate funds transfers between bank accounts, and they work much more quickly than a paper check since they skip all the manual steps.

- Traveler’s checks: These are prepaid checks that you can buy in multiple currencies for use while travelling. With the rise of international payment networks, they’re quickly going out of style, but are still accepted by many tourist-oriented businesses. They are insured against theft, destruction, and loss, making them a fairly safe option to carry.

- Payroll checks: These are checks made out from businesses to their employees. They are essentially the same as regular checks, but include a little more tax information and are generally regarded as a little more trustworthy since they are backed by a company rather than an individual.

-

Other types of checks also exist, but they are less common and unlikely to pop up in an average transaction.

Do people still use checks?

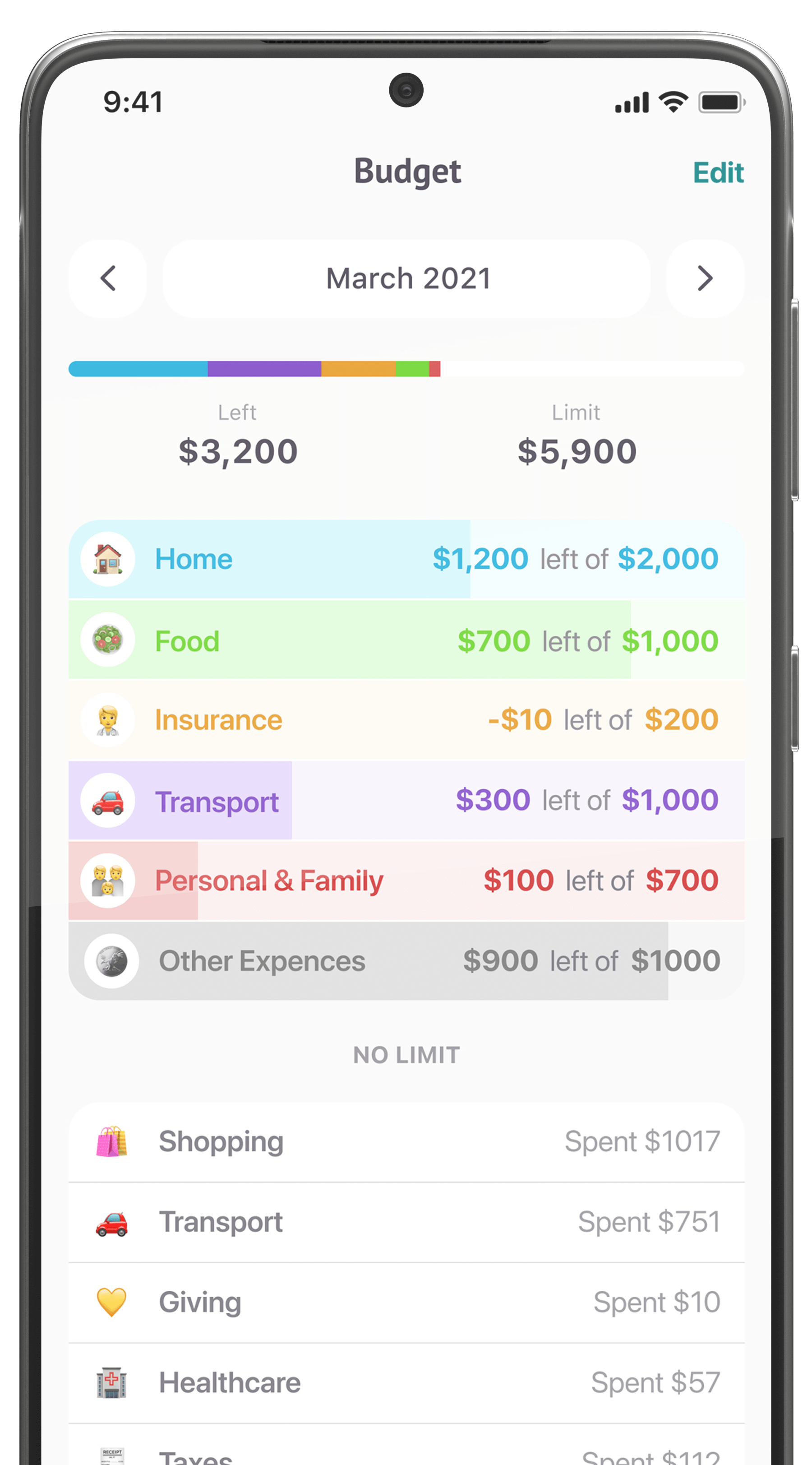

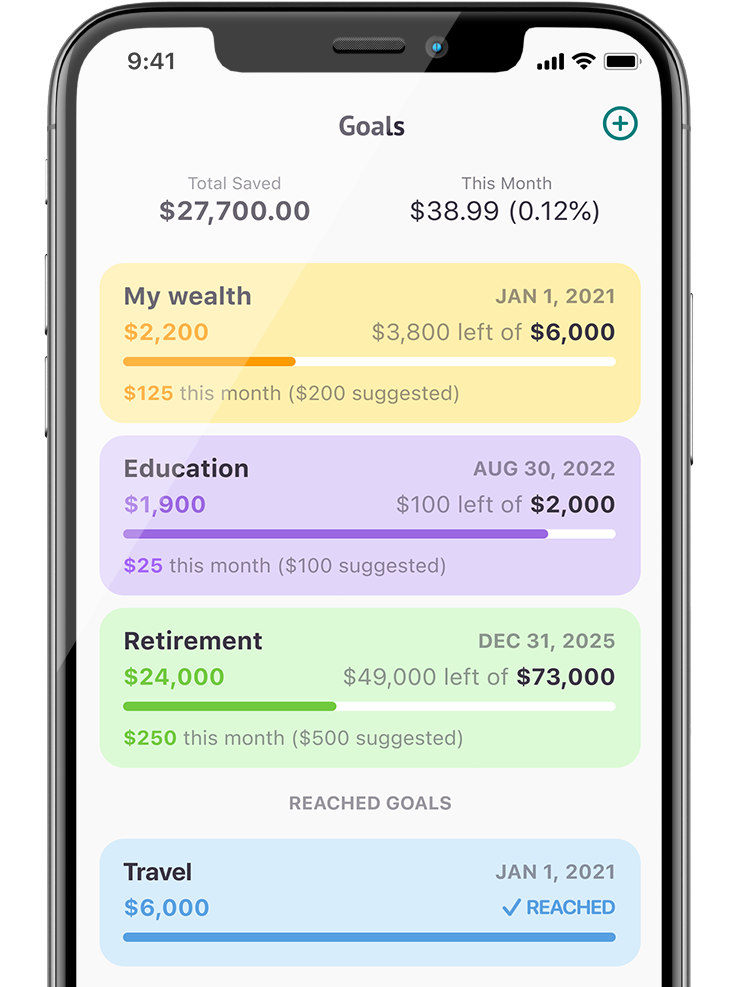

Checks are still widely used in the U.S for payroll, rent payments, government benefits, medium-sized money transfers, paying taxes, and the rare payment that is more convenient or effective offline. They do have a few advantages: they can have lower fees than credit cards, they enable offline payments, and might be a good way to control your spending (since they’re so unwieldy to use).

The cons outnumber the pros, though: checks are slow, inconvenient, insecure, contain a lot of personal information (name, address, bank information, etc), and have to be physically delivered or mailed. This means their days are most likely numbered, though, as companies continue to upgrade their systems and individuals continue to migrate towards e-checks and other online payment systems. And you probably already have a checking account as it gives access to a lot of other services. If you don’t, you probably should read our tips to get the right checking account for you.